Slovic 1987 - Perception of Risk

Slovic, P. (1987). Perception of risk. Science, 236(4799), 280-285.

Summary

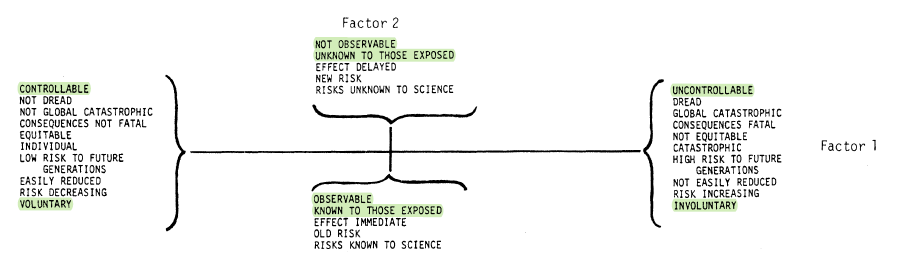

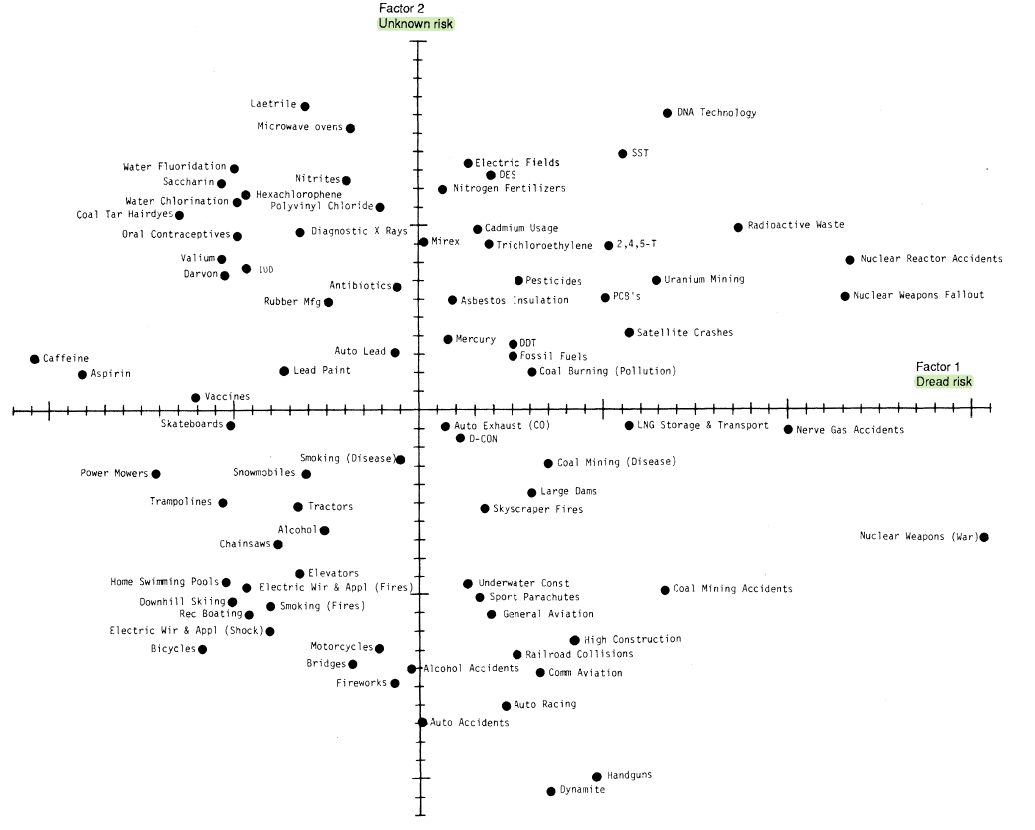

Risk assessment can be heavily influenced by social factors. Downplaying certain risk factors and highlighting others can be used as a method of controlling a group (e.g., a xenophobic leader might refer to immigrants as “drug dealers, rapists and murderers”). Interestingly, experts and lay people tend to view risk differently. Expert risk assessment (at least in the cited study, which is specifically about risk assessment and technology) tended to correlate to “technical estimates of annual fatalities.” The risk assessment of lay people tended to incorporate more dimensions, like “catastrophic potential” and “threat to future generations.” Factor analysis of risk questionnaire studies revealed two key factors - observability / known to not observable / unknown and controllable to uncontrollable. There are several traits additionally associated with those factors (see Fig 1.), though the aforementioned ones seem to be predominant.

The author compares accidents to stones dropped in a pond. The example of Three Mile Island is cited. In that incident, no one died (so experts might have categorized it as low risk), but that incident resulted in massive regulation being imposed on the nuclear industry (the social pressure was high to do so, because lay people evaluated the risk as large). Some events cause small ripples, while some cause large ripples. Unfortunately, experts aren’t always accurate in predictions of situations that will really make waves. The “signal potential” of an accident seems to be a function of where it lies in the factor space.

A large accident with many fatalities in a “known” system (like a train wreck) might not cause social outrage, but a small accident in an “unknown” system might (as in the case of a recombinant DNA lab). The unknown nature of the second accident, because it is poorly understood or perhaps not demonstrably safe, could be perceived as having massive risk. These are referred to as “higher order impacts” - referring to impacts beyond the immediate situation.

Application

Methodologically, the idea of providing many stimuli and then using factor analysis for capturing covariance is interesting, especially as an exploratory first step in scale validation. Once the initial factors have been identified, then items can be developed to flush them out fully. It seems like normally this step is skipped, with researchers instead generating a bunch of survey items and using factor analysis to whittle them down. It seems like using this first step would result in a more robust scale.

A takeaway for managers would be involving as many viewpoints as possible when assessing risk. If implementing new factory equipment, don’t just talk to the VP, talk to the foreman and the actual line workers.

This research also made me think about the concept of demonstrability as a function of the availability heuristic. I don’t believe there is much research done on this, and it represents a possible avenue for future research.